Translate this page into:

Incidence, risk factors, microbiological profile and outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia in paediatric intensive care unit

*Corresponding author: H. S. Rajani, Department of Pediatrics, JSS Medical College, JSS Academy of Higher Education And Research, JSS Hospital, Mysuru, Karnataka, India. drrajanihs@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Usha Rani D, Rajani HS, Nagaraj R, Kiran HS. Incidence, risk factors, microbiological profile and outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia in paediatric intensive care unit. Karnataka Paediatr J. 2025;40:8-13. doi: 10.25259/KPJ_46_2024

Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to assess the incidence, risk factors and outcomes associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in PICU patients as well as analyse the microbiological characteristics of VAP.

Material and Methods

A 20-month prospective observational study was conducted in the PICU of a tertiary hospital. The study included all children requiring mechanical ventilation (MV) for more than 48 hrs, until 100 patients were enrolled. Information on demographics, clinical features, laboratory findings, imaging, treatment and outcomes was documented. VAP was diagnosed using centers of disease control/national nosocomial infections surveillance (CDC/NNIS) criteria and confirmed through endotracheal (ET) aspirate cultures (≥105 colony forming unit (CFU)/mL). Patients with VAP were compared to those without regarding risk factors, clinical details, treatment and outcomes, including length of stay and mortality. All participants were followed until discharge or death.

Results

VAP incidence was 51% based on CDC/NNIS criteria, with microbiological confirmation in 41% of cases. Nearly half of the cases were early-onset VAP, and the incidence density was 57.4 episodes/1000 ventilator days. Younger children (≤1 year) were disproportionately affected (60.8%). Gender had no significant impact on VAP development. Respiratory conditions were the most common predisposing factors, though primary diagnoses did not significantly affect VAP rates. Risk factors such as nasogastric feeding during MV, prior antibiotic use, proton pump inhibitors and uncuffed ET tubes were significantly associated with VAP (P < 0.01). The VAP-associated mortality rate was 33.3%, similar to the 18.4% mortality in nonVAP pneumonia. Most VAP-related deaths were linked to Gram-negative bacteria, primarily Acinetobacter, Klebsiella and Escherichia coli. The VAP group had significantly longer PICU and hospital stays compared to the non-VAP group.

Conclusions

VAP is a frequent and serious complication in mechanically ventilated PICU patients, significantly increasing the duration of hospitalisation and intensive care unit (ICU) stays. While it does not markedly raise mortality rates compared to non-VAP pneumonia, it emphasises the need for better prevention, early diagnosis and management strategies in the PICU setting.

Keywords

Endotracheal aspirate culture

Incidence

Mechanical ventilation

Risk factors

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a type of hospital-acquired pneumonia that develops in patients who have been mechanically ventilated for at least 48 h, either through an endotracheal tube (ETT) or a tracheostomy tube. In paediatric intensive care units (PICUs), it ranks as the second most frequent nosocomial infection after bloodstream infections and is a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality amongst hospital-acquired infections.[1-3]

Despite advancements in managing patients reliant on mechanical ventilation (MV), VAP continues to affect 8–28% of those on ventilators.[4,5] In developed countries, the prevalence of VAP amongst ventilated PICU patients is estimated at 3–10%.[6] However, studies from India report much higher rates, ranging from 6% to 46%.[7] Understanding the primary bacterial pathogens causing VAP and their antibiotic resistance patterns is essential for guiding effective treatment strategies. In addition, identifying risk factors that influence VAP outcomes can help reduce the associated morbidity and mortality and contribute to the development of preventive measures.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This prospective observational study was conducted in the PICU of a tertiary care hospital over 20 months. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee before commencing the research. The study included PICU patients aged 1 month–19 years who required conventional MV for more than 48 hrs. Patients who had been intubated and ventilated at other hospitals before being admitted to the PICU were excluded from the study.

The sample size was calculated using an online tool (Raosoft Sample Size Calculator) based on a previously reported VAP incidence of approximately 7% (range: 3–10%).[8] To achieve a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error, a minimum sample size of 92 was determined, which was rounded up to 100 participants. Eligible patients were enrolled consecutively after obtaining informed consent from their parents or guardians.

A structured data collection sheet was used to record demographic details such as age and sex, along with clinical information, including admission date, reason for admission (medical or surgical), comorbidities, nutritional and immunological status, socioeconomic status, primary diagnosis, PRISM III score, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, duration of MV, length of ICU stay, the occurrence of VAP, causative pathogens, prior antibiotic use (<48 hrs vs. >48 hrs before MV), patient positioning (supine or semi-recumbent), reintubation events, nasogastric feeding, use of medications (e.g., inotropes, sedatives, paralytics and peptic ulcer prophylaxis) and patient outcomes (discharge, improvement or death).

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, including amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, amikacin or piperacillin-tazobactam, were initiated based on PICU protocols and underlying conditions either before or immediately after initiating MV. Oral hygiene care was done with suction to remove excess fluid and saline swabs were used. Chlorhexidine mouthwashes were used twice daily. Reusable ventilator circuits were used. They were changed after 72 hrs or when it was visibly soiled. Reusable components that came in contact with the patient’s mucous membranes or contaminated with their respiratory secretions were cleaned and disinfected. Wearing masks and gloves and washing hands before and after handling the circuit was practised.

A baseline chest X-ray was performed post-intubation, with additional imaging and blood cultures conducted for patients with suspected VAP. Endotracheal aspirates (ETAs) were collected aseptically using a mucus extractor connected to a suction machine. The collected samples were sent to the microbiology laboratory, where they were cultured using blood, chocolate and MacConkey agars, with fungal cultures conducted when indicated.

VAP was diagnosed using the centers of disease control/national nosocomial infections surveillance (CDC/NNIS) criteria (2003)[2] and confirmed by a positive culture showing ≥105 colony forming unit (CFU)/mL. Samples yielding ≤105 CFU/mL or showing no growth that did not meet the criteria for nosocomial pneumonia were classified into the no-VAP group. Antibiotic regimens were adjusted based on the susceptibility patterns of the identified organisms.

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. Descriptive statistics, such as percentages and medians with interquartile ranges, were used to summarise the data. Categorical variables were analysed with the Chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Variables significantly associated with VAP in univariate analysis were further analysed using multiple logistic regression to identify independent risk factors.

RESULTS

During the study, 1330 children were admitted to the PICU, of which 237 required MV. Of these, 100 patients met the study criteria and were analysed, contributing to a total of 889 ventilator days. Based on CDC/NNIS criteria, 51% of the patients developed VAP, while 49% did not [Table 1]. In the VAP group, 60.8% of the patients were ≤1 year old, and 21.6% were aged >1–5 years. Amongst non-VAP patients, 34.7% were >1–5 years old, followed by 32.7% aged ≤1 year. Overall, 69% of the study participants were male (male-to-female ratio: 2.2:1). In the VAP group, 72.5% were male, compared to 65.3% in the non-VAP group. Respiratory conditions were the leading cause of MV in both groups (23.5% in VAP vs. 28.6% in non-VAP patients). Sepsis was the second most common diagnosis in the VAP group (15.7%), while sepsis and dengue fever were equally common in the non-VAP group (15.7% each). There was no statistically significant difference in primary diagnoses between the two groups [Table 2]. Positive ETAs cultures were obtained in 80.4% of clinically diagnosed VAP patients. Most isolates were Gram-negative bacteria (91.8%), with Acinetobacter baumannii being the most common, followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. Early VAP was predominantly caused by Acinetobacter, E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, while late VAP was most associated with K. pneumoniae. A single case of early VAP involved Candida tropicalis. Univariate analysis revealed significant associations (P < 0.05) between VAP development and the following factors: Nasogastric feeding during MV, antibiotic use for more than 48 h before initiating MV, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use (with a longer median duration in the VAP group, 10 days, compared to the nonVAP group, 6 days), the use of uncuffed ETT and reintubation during ventilation [Table 3].

| VAP | n=100 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 51 | 51 |

| No | 49 | 49 |

VAP: Ventilator-associated pneumonia, CDC: Centers of disease control, NNIS: National nosocomial infections surveillance

| System involved | Total | VAP | No VAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=100 (%) | n=51 (%) | n=49 (%) | |

| RS | 26 (26) | 12 (23.5) | 14 (28.6) |

| Sepsis | 20 (20) | 8 (15.7) | 12 (24.5) |

| Dengue fever | 19 (19) | 7 (13.7) | 12 (24.5) |

| CNS | 14 (14) | 9 (17.6) | 5 (10.2) |

| Hydrocarbon poison | 4 (4) | 3 (5.9) | 1 (2.0) |

| OP poisoning | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.1) |

| Paraquat poisoning | 1 (1) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) |

| CVS | 6 (6) | 6 (11.8) | 0 (0) |

| Head injury | 4 (4) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (4.1) |

| CVS | 2 (2) | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0) |

| Tetanus | 1 (1) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) |

VAP: Ventilator-associated pneumonia, MV: Mechanical ventilation, CNS: Central nervous system, RS: Respiratory system, CVS: Cardiovascular system, OP: Organophosphate.

| Risk factors | VAP | No VAP | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n(%) | n(%) | ||

| Host factors | |||

| GCS | |||

| <7 | 20 (50.0) | 20 (50.0) | 0.6 |

| >7 | 31 (51.8) | 29 (48.2) | |

| Nutritional status | |||

| PEM | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | 0.3 |

| Adequate | 46 (52.3) | 42 (47.7) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Yes | 21 (47.7) | 23 (52.3) | 0.9 |

| No | 30 (53.6) | 26 (46.4) | |

| Treatment-related risk factors | |||

| Requirement of paralytic agents | |||

| Yes | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) | 0.6 |

| No | 43 (50.0) | 43 (50.0) | |

| Sedation | |||

| Yes | 51 (51.0) | 49 (49.0) | NA |

| Inotropic support | |||

| Yes | 45 (52.3) | 41 (47.7) | 0.3 |

| No | 6 (42.9) | 8 (57.1) | |

| Aspiration of subglottic secretions | |||

| Yes | 51 (51.0) | 49 (49.0) | NA |

| Antibiotics before MV | |||

| Yes | 43 (61.4) | 27 (38.6) | 0.001 |

| No | 8 (26.7) | 22 (73.3) | |

| Antibiotic use <48 h before MV | |||

| Yes | 17 (44.7) | 21 (55.3) | 0.3 |

| No | 34 (54.8) | 28 (45.2) | |

| Antibiotic use >48 h before MV | |||

| Yes | 26 (81.3) | 6 (18.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 25 (36.8) | 43 (63.2) | |

| Proton pump inhibitors | |||

| Yes | 51 (54.8) | 42 (45.2) | 0.005 |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | |

| NG feeding | |||

| Yes | 17 (73.9) | 6 (26.1) | 0.01 |

| No | 34 (44.2) | 43 (55.8) | |

| Type of ET tube | |||

| Cuffed | 13 (31) | 29 (69) | <0.001 |

| Uncuffed | 38 (65.5) | 20 (34.5) | |

| Reintubations | |||

| Yes | 27 (77.1) | 8 (22.9) | <0.0001 |

| No | 24 (36.9) | 41 (63.1) | |

VAP: Ventilator-associated pneumonia, GCS: Glasgow coma scale,

MV: Mechanical ventilation, ET: Endotracheal, PEM: Protein energy malnutrition, NG: Nasogastric feeding, NA: Not applicable

27 cases in the VAP group and 8 cases in the non-VAP group had re-intubations, which was significant (P < 0.0001). The odds of developing VAP were 5.6 times higher with re-intubation compared to no re-intubation. The maximum number of cases (22 cases) had 1–2 re-intubations, with 14 (63.6%) in the VAP group and 8 (36.4%) in non-VAP cases. Ten patients in the VAP group had 3–4 and 3 patients had 5–6 re-intubations. With a higher number of re-intubations, there was a significant increase in the chances of developing VAP. None of them had spontaneous extubation.

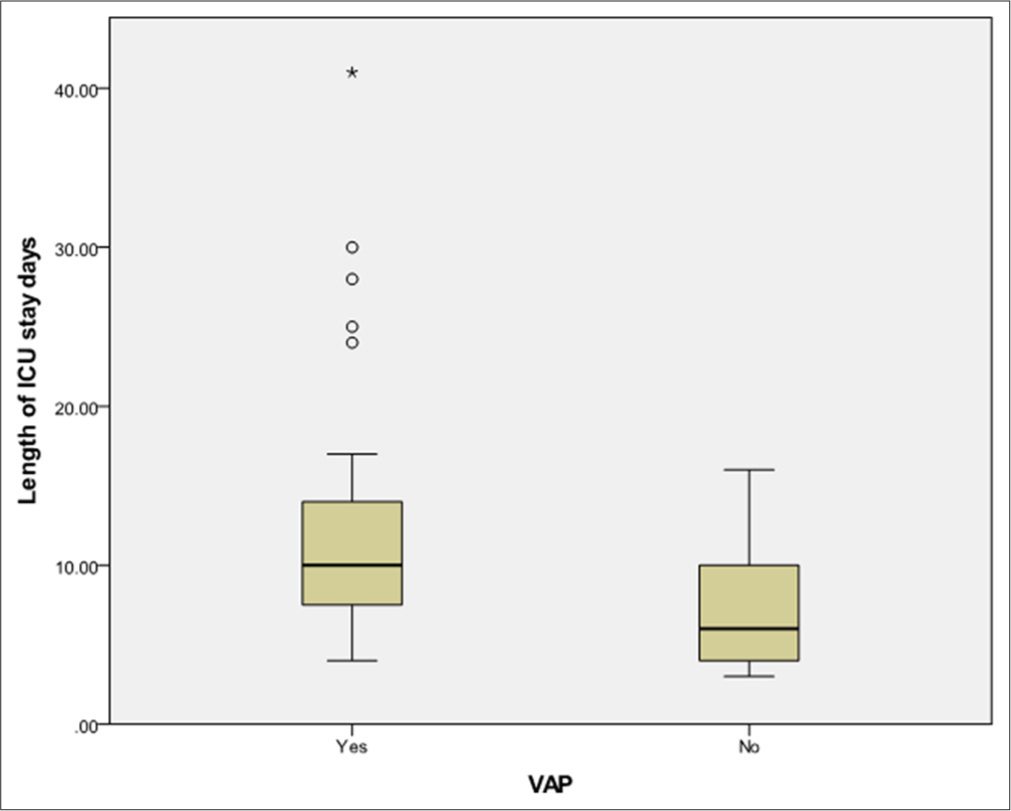

Positive blood cultures were reported in 11 patients with VAP and 1 patient without VAP. Amongst the isolates in the VAP group were Staphylococcus hominis (2 cases), Staphylococcus aureus (1 case) and Staphylococcus haemolyticus (1 case). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was detected in a single patient in the non-VAP group. The mortality rate was higher in the VAP group (33.3%) compared to the nonVAP group (18.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.3). Amongst VAP cases, early VAP had a mortality rate of 39.3%, while late VAP had a rate of 26.1%. Improvement rates were 35.7% for early VAP and 55.1% for late VAP, but these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.3). VAP patients had a significantly longer ICU stay, with a median duration of 10 days (range: 3–45 days) compared to 6 days (range: 3–16 days) for nonVAP patients (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

MV is a vital component of modern intensive care, but its use is associated with a significant risk of VAP. Identifying patients at high risk and recognising modifiable risk factors can aid in creating strategies to prevent infections and improve institutional protocols.

In the current study, the VAP incidence was 51%, higher than previous Indian studies reporting a range from 6.03% to 46.4%, and international studies[9-11] from developed nations, which show a range of 3–31%. These variations may be attributed to differences in diagnostic criteria, patient population and underlying conditions necessitating ventilator support. The higher incidence in this study may stem from the use of the CDC/NNIS criteria, as opposed to relying on clinical features combined with positive microbiological cultures from endotracheal (ET) aspirates, which other studies often use. When restricted to cases with significant microbiological growth in ET aspirates, the VAP incidence in this study was 41%, aligning with rates from other research, such as Awasthia et al. (36.2%)[10] and Payal et al. (46.4%).[12] In addition, most cases involved early-onset VAP.

The incidence density of VAP in this study was 57.4 episodes/1000 ventilator days. This figure surpasses the reported range of 1–63 episodes/1,000 ventilator days observed in both paediatric and neonatal populations. Factors influencing these rates include geographical location, hospital type and the economic status of the country.[13] For instance, reported rates include 36.2% in Indian paediatric ICUs[10] and 31.8/1,000 ventilator days in Egypt.[14]

The study also analysed VAP risk factors by comparing patients with and without VAP. Amongst patients with VAP, 60.8% were under 1 year old, and a statistically significant difference in age was noted between the VAP and non-VAP groups (P = 0.03). Despite the predominance of male patients in both groups, the sex distribution was not significantly different (P = 0.4), with a male-to-female ratio of 2.6:1 in the VAP group, consistent with findings by Patra et al.[8] Most participants in both groups came from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, but socioeconomic status did not significantly affect VAP occurrence.

Other potential factors, such as the primary diagnosis, GCS score, nutritional status and comorbidities, showed no significant correlation with VAP in this study. These findings align with those of Vedhavathy and Sangamesh[11], who reported similar distributions of age, sex and MV indications between VAP and non-VAP groups. However, contrasting evidence from Galal et al.[15] suggests younger age (<1 year) and female sex as significant risk factors for VAP, along with specific diagnoses such as coma and multiple organ failure. Similarly, Amanti[16] identified immune status as a significant factor, whereas Patra et al.[8] found no link between age, malnutrition and VAP risk.

This study found no significant association between surgical procedures, including central line placement, bronchoscopy, tracheostomy, or thoracostomy, and the development of VAP. However, research by Vedhavathy and Sangamesh[11] reported that tracheostomy and the presence of central venous lines were significantly linked to VAP occurrence. Similarly, Elward et al.[6] observed that surgical interventions significantly contributed to VAP development.

Reintubation emerged as a critical risk factor for VAP. The study highlighted that the probability of developing VAP increased with a higher number of reintubations, particularly in cases of unplanned reintubation or multiple attempts. Prior studies, including those by Elward et al.,[6] Patra et al.,[8] Nemat B et al.[17] and Khalid Amro,[18] identified reintubation as an independent risk factor, with Patra et al.[8] reporting a strong statistical association (P < 0.001).

The use of cuffed ETT was associated with a significant reduction in VAP incidence in this study (P < 0.001). Conversely, findings from the Vedavathy S study[11] indicated no significant difference in VAP rates based on the type of ETT used.

In this study, factors such as the use of paralytic agents during intubation, sedatives and inotropes for haemodynamic stabilisation did not significantly contribute to VAP risk. However, prolonged use of antibiotics (beyond 48 h), PPIs and nasogastric (NG) feeding was significantly associated with an increased risk of VAP (P < 0.05). Previous studies by Vedavathy S[11] and Patra et al.[8] found that NG tubes and stress ulcer prophylaxis were not significant risk factors, while Elward et al.[6] reported H2 receptor blockers as contributing factors. In addition, early initiation of enteral feeding (on day 1 of MV) was linked to a higher risk of VAP compared to delayed feeding (starting on day 5).

Microbiological findings revealed that 80.4% of clinically diagnosed VAP cases had positive cultures from ETAs, with Gram-negative bacteria accounting for 91.8% of isolates. The predominant organisms were A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae and E. coli. These results align with studies by Balasubramanian and Tullu[7] and Patra et al.,[8], although their findings identified Pseudomonas as the second most common isolate. In contrast, Staphylococcus aureus was more prevalent in studies from Europe and North America. Many pathogens in this study exhibited multidrug resistance, presenting significant treatment challenges. Polymicrobial infections were detected in some cases, with frequent co-isolation of Acinetobacter and E. coli.

The mortality rate amongst VAP patients in this study was 33.3%, comparable to rates reported in other studies, including those by Mahantesh et al. (28.38%),[19] Patra et al. (31.8%),[8] Balasubramanian and Tullu (42.8%)[7] and Amanati et al. (47%).[16] No significant difference in mortality was observed between early-onset VAP (39.3%) and late-onset VAP (26.1%). In addition, the mortality rate in VAP patients was not significantly higher than in non-VAP patients (18.4%, P = 0.3).

The median duration of PICU stay (10 vs. 7.5 days) [Figure 1] and overall hospital stay (14 vs. 12 days) in the VAP group were significantly longer compared to the non-VAP group, consistent with findings from prior studies.[6,8,20,21] In contrast, the study by Galal et al.[15] reported shorter PICU stays (11 vs. 17 days) and shorter MV durations (8 vs. 12 days) in patients with VAP, attributed to reduced median survival time leading to earlier mortality.

- Box and whisker plot for the length of intensive care units stay (days) between ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and non-VAP patients. ICU: Intensive care unit, Circle: Mild outliers, Star: Extreme outlier.

Amongst the 17 VAP-related deaths in the current study, 94% were due to Gram-negative bacterial infections. Acinetobacter was responsible for nearly half of these fatalities, followed by Klebsiella (29.4%), E. coli (11.7%) and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (5.9%). Similarly, in the study conducted by Patra et al.,[8] all deaths in patients with nosocomial pneumonia were caused by Gram-negative bacteria, with Pseudomonas accounting for 57.1% of fatalities.

CONCLUSION

Although VAP was associated with adverse outcomes, it did not significantly contribute to overall mortality. Increased awareness of these risk factors is essential for reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with VAP.

Further research is warranted to understand better the risk factors and diagnostic criteria for VAP in paediatric intensive care settings.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Jagadguru Sri Shivarathreeswara Medical College Institutional Ethics Committee, number JSSMC/PG/130/2016-17, dated 24th November 2016.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- A national point prevalence survey of pediatric intensive care unit-acquired infections in the United States. J Pediatr. 2002;140:432-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated pneumonia, 2003: Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53:1-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia: Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:637-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis, assessment of severity, initial antimicrobial therapy, and preventive strategies. A consensus statement. American Thoracic Society, November 1995. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1711-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Survival in patients with nosocomial pneumonia: Impact of the severity of illness and the etiologic agent. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1862-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit patients: Risk factors and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2002;109:758-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Study of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a pediatric intensive care unit. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:1182-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosocomial pneumonia in a pediatric intensive care unit. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:511-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized trial of diagnostic techniques for ventilator-associated pneumonia. N Engl Med. 2006;355:2619-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longer duration of mechanical ventilation was found to be associated with ventilator-associated pneumonia in children aged 1 month to 12 years in India. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:62-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical study of ventilator associated pneumonia in a tertiary care centre. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2016;3:432-41.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A study on ventilator associated pneumonia in pediatric age group in a tertiary care hospital, Vadodara. Natl J Med Res. 2012;2:318-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia in neonates, infants and children. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3:30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Device-associated infection rates in adult and paediatric intensive care units of hospitals in Egypt. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) findings. J Infect Public Health. 2012;5:394-402.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventilator associated pneumonia: Incidence, risk factors and outcome in paediatric intensive care unit at Cairo University Hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:SC06-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill children undergoing mechanical ventilation in pediatric intensive care unit. Children. 2017;4:56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Does reintubation increased risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) in pediatric intensive care unit patients? Int J Pediatr. 2015;3:411-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reintubation increases ventilator-associated pneumonia in pediatric intensive care unit patients. Rawal Med J. 2008;33:145-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia in paediatric intensive care unit at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health. Indian IJIRM. 2017;2:36-41.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial nosocomial pneumonia in paediatric intensive care unit. J Postgrad Med. 2000;46:18-22.

- [Google Scholar]