Translate this page into:

Senior-Loken syndrome: A case report

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Duraiswamy A, Babilu CO. Senior-Loken syndrome: A case report. Karnataka Paediatr J 2020;35(1):57-60.

Abstract

Senior-Loken syndrome refers to a combination of nephronophthisis and retinal dystrophy. Nephronophthisis progresses to end-stage renal disease during the second decade. The retinal lesions vary from severe infantile onset retinal dystrophy to milder pigmentary retinopathy. There is a spectrum of associated features, including skeletal, dermatological, and cerebellar anomalies. Here, we report a case of first genetically proven Senior-Loken syndrome in India, who presented with growth failure, polyuria, polydipsia, nystagmus, and defective night vision.

Keywords

Senior-Loken

Nephronophthisis

Retinal dystrophy

INTRODUCTION

Renal nephronophthisis, a renal ciliopathy, is a disease causing cystic kidneys or renal cystic dysplasia. It is the most common genetic cause of chronic kidney disease in the first two decades of life.[1]

Retinal dystrophy is one of the extrarenal associations of nephronophthisis. It manifests as congenital amaurosis of the Leber type or late-onset pigmentary retinal degeneration. It begins in childhood or early adolescence and produces a visual handicap ranging from night blindness to functional blindness.[2,3]

Senior-Loken syndrome refers to a combination of nephronophthisis and retinal dystrophy. It was first described in 1961 by Senior et al.[4] who described a family in which 6 of 13 children had nephronophthisis and tapetoretinal degeneration. Loken et al.[5] described the same condition in two siblings who had blindness and severe renal failure with renal tubular atrophy and dilatation on biopsy. This syndrome contributes to 10–15% of overall nephronophthisis, a group of illnesses affecting 1 in 50,000 births. The onset is insidious, and most cases do not present until end stage renal failure.

There have been 150 cases of Senior-Loken syndrome reported worldwide. Few cases are also reported from India based on typical renal, retinal changes, and a consistent clinical picture.[1,6-10] The Indian cases reported have not been genetically proven. Our case is the first genetically proven case of Senior-Loken syndrome in India.

CASE REPORT

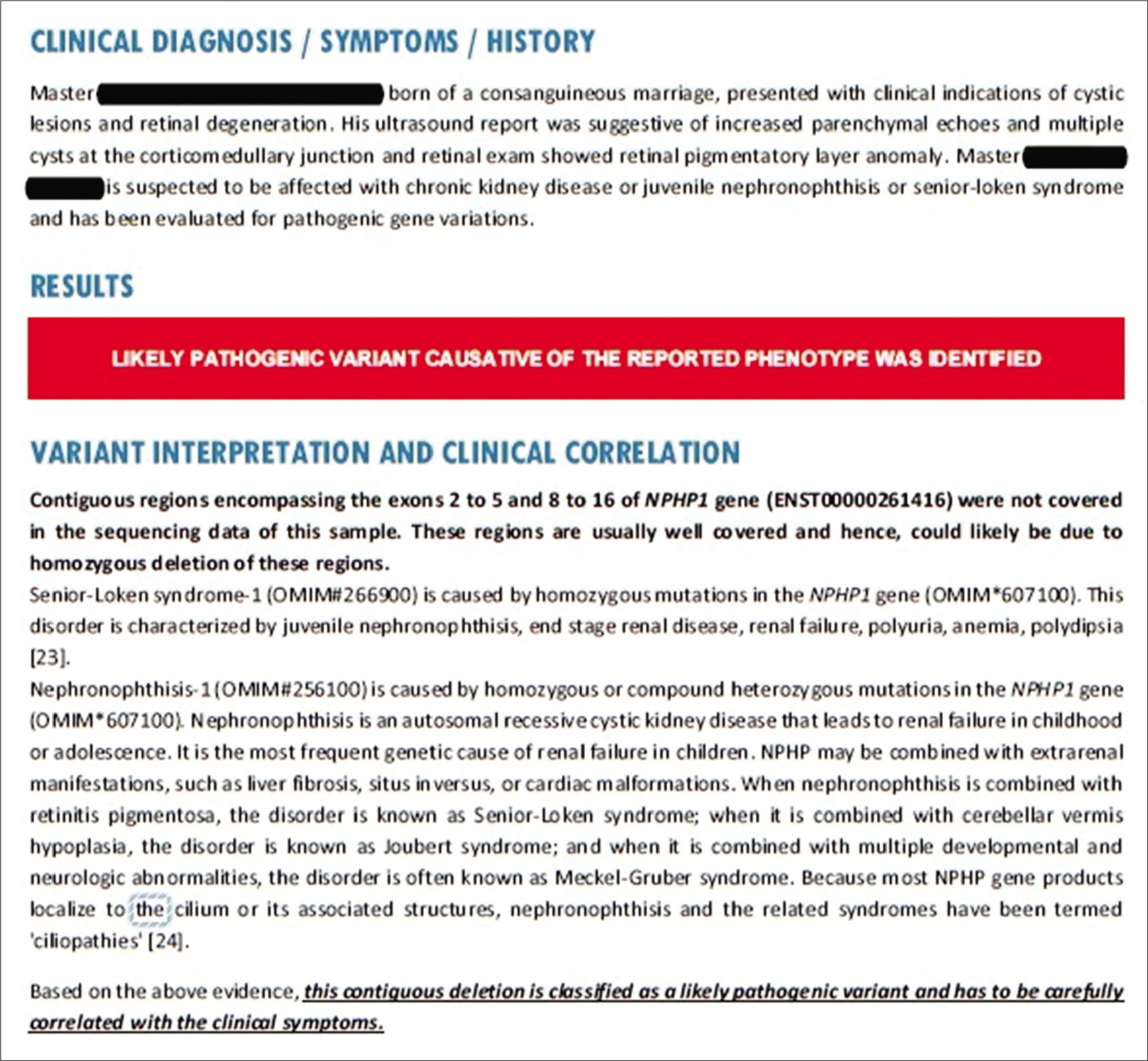

A 15-year-old boy, first born out of third degree consanguineous marriage, presented with easy fatigability, defective night vision, polyuria, polydipsia, growth failure, and unsteadiness of gait which is worsening at night. On examination, he was pale with generalized edema, had a pulse rate of 90/min and no radiofemoral delay, blood pressure of 144/110 mmHg (Stage 2 hypertension: AAP guidelines 2017), respiratory rate of 20/min, and SpO2 of 96% with room air and had no dysmorphic features. His height and weight were 135 cm and 27 kg, respectively (<3rd percentile: IAP growth charts 2015). Systemic examination was normal, with no cerebellar signs except for rapid fine horizontal nystagmus. A detailed ophthalmology evaluation revealed retinal pigmentary epithelial changes along with evidence of dystrophy confirmed by electroretinogram (ERG). Investigations revealed hemoglobin: 5.2 g/dl (10.8–15.6 g/dl), normocytic normochromic blood picture, calcium: 5.7 mg/dl (7.6– 11 mg/dl), magnesium: 2.26 mg/dl (1.7–2.55 mg/dl), phosphorus: 8.7 mg/dl (3–5.4 mg/dl), parathyroid hormone: 664.4 ng/L (4.5–36 ng/L), 25-hydroxyvitamin D: 23.64 ng/ml (30–47 ng/ml), creatinine: 14.9 mg/dl (0.2–0.87 mg/dl), and urea: 265 mg/dl (10–48 mg/dl). Urine complete analysis revealed isosthenuria and ultrasound KUB showed bilateral shrunken kidney with increased renal parenchymal echoes and multiple cysts at corticomedullary junction. MRI brain was not done. 2D ECHO showed a normal heart and normal great vessel anatomy and function. Suspecting Senior-Loken syndrome, clinical exome sequencing was done which revealed contiguous homozygous deletion encompassing exons 2–5 and 8–16 of NPHP1 gene, confirming the disease [Figure 1]. The child was under renal replacement therapy, antihypertensives, and other supportive measures and later underwent renal transplantation.

- The genetic report confirming the diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Nephronophthisis is characterized by chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis that progresses to end-stage renal disease during the second decade.[11] At least 14 different NPHP genes have been identified as causes for nephronophthisis: Nephrocystin genes including (NPHP1, NPHP2, NPHP3, NPHP4, NPHP5, NPHP6, NPHP7, NPHP8 and NPHP9, NPHP10, NPHP11, NPHP12, NPHP13, and NPHPL1)[1] and mutation in IQCB1 (also called NPHP5) identified as the most frequent cause.[8]

Senior-Loken syndrome also known as hereditary renal- retinal syndrome or renal-retinal dysplasia, is a rare autosomal recessive disorder[1] caused by mutation in NPHP1 gene. It is a progressive ciliopathy affecting the kidney and retina primarily.

Nephronophthisis is caused by dysfunction of primary cilia, which are sensory organelles that connect mechanosensory, visual, osmotic, and other stimuli for cell cycle control leading to multisystem involvement and broad spectrum of extrarenal manifestations[1] which includes retinal degeneration, oculomotor apraxia (Cogan type), coloboma, aplasia of cerebellar vermis, polydactyly, and neonatal tachypnea (Joubert syndrome); cranioectodermal dysplasia and electroretinal abnormalities (Sensenbrenner syndrome).[8]

Severe infantile, juvenile, and adolescent are the three clinical types of nephronophthisis.[12] These are described based on the age of onset of end-stage renal disease in these patients.[12] Early symptoms include polyuria, polydipsia, and enuresis due to a concentrating defect. The disease usually progresses to end-stage renal disease before 20 years, although late onset in the third decade has also been reported.[13] The ultrasonographic findings of juvenile nephronophthisis may be normal or may show increased renal parenchymal echogenicity, poor corticomedullary differentiation, a small kidney, or medullary cysts.[14] Renal histology is characterized by the triad of interstitial infiltration, renal tubular cell atrophy with cyst development, and renal interstitial fibrosis.[15] Primary management depends on delaying the progression of renal failure and the need for dialysis and transplantation.[2] Renal transplantation is the preferred treatment as disease does not recur in the transplanted kidney.[16] Vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists, which alter the cystogenesis and progression of the disease have been tried.[2]

The ocular manifestation may be in the form of tapetoretinal degeneration, most common form, characterized by progressive choroid and retinal degeneration, Leber type congenital amaurosis, or late-onset pigmentary retinal degeneration.[3] It can also be manifested in the form of cataracts, Coats disease, or even keratoconus. ERG typically shows reduced rod cell function and also helps in early diagnosis of the disease, even before the symptom onset or fundoscopic examination. Annual eye examination is recommended to monitor the progression of retinal involvement of the disease.[2] Management of the ocular disease is primarily supportive.

Patients having this disorder require dialysis or kidney transplant by the time they reach adolescence. Nephronophthisis patients must have a periodical ophthalmological evaluation with an ERG. Children with primary tapetoretinal degeneration should have routine measurements of blood pressure, urinary concentrating ability, and renal ultrasound scan. Early diagnosis, hypertension control, and protein intake restriction may delay dialysis.[9]

Proving a genetic diagnosis of the disease offers help in both the patient management and in genetic counseling for parents to prevent recurrence in subsequent pregnancies.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med. 2003;9:1323-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior-Loken syndrome (nephronophthisis and tapeto-retinal degeneration): A study of 8 cases from 5 families. Clin Nephrol. 1976;5:14-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Juvenile familial nephropathy with tapetoretinal degeneration. A new oculorenal dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1961;52:625-33.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hereditary renal dysplasia and blindness. Acta Paediatr. 1961;50:177-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior-Loken syndrome with unusual manifestations. J Assoc Physicians India. 1998;46:470-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Twins with Senior-Loken syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:1041-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior-Loken syndrome with rare manifestations: A case report. Eurasian J Med. 2013;45:128-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypomorphic mutations in meckelin (MKS3/TMEM67) cause nephronophthisis with liver fibrosis (NPHP11) J Med Genet. 2009;46:663-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sector retinitis pigmentosa in juvenile nephronophthisis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980;64:124-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound findings in juvenile nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1996;10:22-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The nephronophthisis complex. A clinicopathologic study in children. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1982;394:235-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children with chronic renal failure in the Federal Republic of Germany: I. Epidemiology, modes of treatment, survival. Arbeits-gemeinschaft fur padiatrische nephrologie. Clin Nephrol. 1985;23:272-7.

- [Google Scholar]