Translate this page into:

The entirety of paediatric osteoarticular infections

*Corresponding author: Harshini T. Reddy Department of Paediatric Infectious Diseases, Manipal Hospitals, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. hachutr.n@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Reddy HT, Shenoy B. The entirety of paediatric osteoarticular infections. Karnataka Paediatr J. 2024;39:121-4. doi: 10.25259/KPJ_21_2023

Abstract

Bone and joint infections are the important cause of morbidity and mortality in children which results in deformities and affects motor development of the child. In paediatric practice, early diagnosis and treatment of osteoarticular infections is very important to prevent morbidity and mortality. The main objective of this article is to understand the clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic profile of paediatric osteoarticular infections, which will help in having a basic framework and algorithm for early diagnosis and appropriate management which decreases the morbidity and mortality associated with osteoarticular infections.

Keywords

Osteoarticular infections

Septic arthritis

Osteomyelitis

Paediatric

Arthroscopy

INTRODUCTION

Paediatric osteoarticular infections include osteomyelitis, septic arthritis and a combination of both. The incidence of osteomyelitis varies between 1 and 13/1 lakh children/year[1] in developed countries to 200/1 lakh children/year in low- and middle-income countries and incidence rates of septic arthritis are reported as 4–37/1 lakh population.[2] 1% of paediatric hospital admissions are due to bone and joint infections.[1] Early diagnosis and treatment play a key role in achieving better outcomes and preventing sequelae leading to disabilities. It is important to understand the clinical and diagnostic profile of paediatric osteoarticular infections to know changing trends in every aspect of management as well as to know the significance of laboratory and radiological investigations which will act as a catalyst for early diagnosis and treatment.

CLASSIFICATION

Paediatric osteoarticular infections are classified into:[3]

Osteomyelitis

Septic arthritis

Combination of both.

PREDISPOSING/RISK FACTORS

The following are the probable associations described in osteoarticular infections:

Upper respiratory tract infection – Kingella kingae

Trauma, blunt injury and varicella infections – group A streptococcus

Sickle cell anaemia – Salmonella species

4, Immunodeficiency – Serratia, Aspergillus

Penetrating wounds – Pseudomonas and anaerobes

Animal handling and laboratory work – Brucella, Coxiella

Contact with pulmonary tuberculosis – Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Prematurity, central venous lines and bacteraemia.

AETIOLOGY

The most common etiological agents of bone and joint infections are tabulated below in Table 1.[3]

| Age | Aetiological agent |

|---|---|

| <3 months |

Staphylococcus aureus Escherichia coli and gram-negative bacteria Group B streptococcus Candida albicans Neisseria gonorrhoea(neonate) |

| 3 months–5 years |

Staphylococcus aureus Kingella kingae Group A streptococcus Hemophilus influenzab Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Older child >5-year old |

Neisseria gonorrhoea Staphylococcus aureus Streptococcus pneumoniae |

Pathophysiology

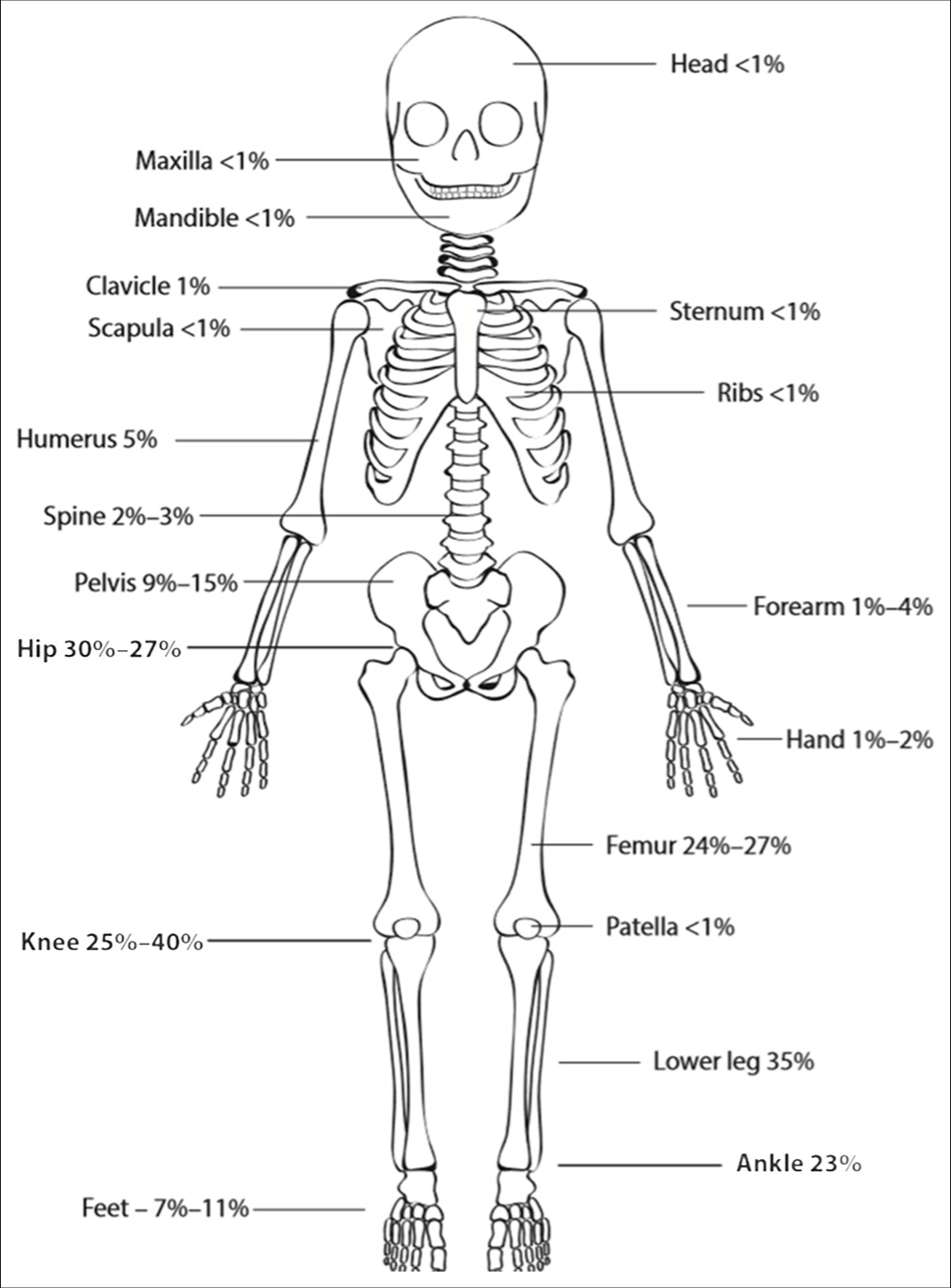

Osteomyelitis affects bone and its medullary cavity. Bone is resistant to infection unless it is subjected to trauma, disruption of blood flow that deprives the bone of normal host immunity, a large inoculum of blood-borne or external microorganisms or a foreign body.[4] Haematogenous inoculation usually starts in the metaphysis, wherein the blood flow is slow in the sinusoidal blood vessels. Inflammatory cells migrate to the area, leading to oedema, vascular congestion and small vessel thrombosis, leading to an increase in intraosseous pressure resulting in impaired blood supply to the medullary canal and periosteum leading to the formation of sequestrum (necrotic bone). Bony tissue attempts to compensate for the tensile stresses caused by infection by creating new bone around the areas of necrosis. This new bone deposition is called an involucrum. Anatomic distribution of osteoarticular infections is shown in Figure 1.[5]

- Anatomic distribution of osteoarticular infections.

Septic arthritis is usually a consequence of haematogenous spread or direct inoculation into the joint. The lack of a basement membrane makes the highly vascular synovium vulnerable to bacterial seeding. From synovium, infection reaches articular cartilage, leading to increased production of synovial fluid, causing joint effusion leading to ischaemic damage of the cartilage.[2]

Clinical features of bone and joint infection in children

The clinical features of bone and joint infections[3] are tabulated in Table 2. The management of bone and joint infections[3] is tabulated in Table 3. The choice of empirical IV antibiotics[3] is tabulated in Table 4.

| Age | Symptoms | Local symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OM | <30 days | Fever Irritability/excessive cry Poor feeding Nonspecific symptoms |

Limb pain Local inflammation Pseudoparalysis If flat bones are involved, no localising signs are found |

| OM | 1 month to 2 years | Vomiting, poor feeding, irritability Fever Severe systemic symptoms due to bacteraemia |

Refusal to bear weight Limping Local inflammation |

| 2 year– 18 years |

Limp Pain Swelling Erythema Older children tend to localise |

||

| SA | 0–18 years | Hot, swollen, immobile peripheral joint Pain on passive joint movement |

OM: Osteomyelitis, SA: Septic arthritis

| Uncomplicated OM/SA | Complicated OM/SA | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Hospitalisation | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Blood tests | CRP, ESR, CBC | ESR, CRP, CBC |

| 3. Bacteriology | Blood Culture: 4 mL in children and 2 mL in neonates: Blood, synovial fluid or bone/tissue sample Consider PCR |

Blood Culture: 4 mL in children and 2 mL in neonates: Blood, synovial fluid or bone/tissue sample Consider PCR |

| 4. Imaging | Osteomyelitis - X-ray, MRI Septic arthritis - USG, MRI (to document any evidence of osteomyelitis) | Osteomyelitis - X-ray, MRI Septic arthritis - USG, MRI; (to document any evidence of osteomyelitis). Bone scan if MRI is not available |

| 5. Surgery | Indications: Effusion, pus, bone destruction and lack of clinical response | Indications: Effusion, pus, bone destruction and lack of clinical response |

| 6. Antibiotic treatment | Discussed separately | |

| 7. Monitoring | When pathogen is not known Switch to oral antibiotic monotherapy based on local microbiology and clinical infectious disease standards Choose oral antibiotics of same spectrum as IV if initial IV response is favourable |

Consider 2nd line or additional antibiotics if gram negative and MRSA are not ruled out. |

| 8. IV to oral switch | Clinical improvement in pain mobility and swelling Afebrile for 24–48 h Decreased CRP (30–50% of highest value) |

Minimum of 1 week of IV therapy and same factors to be considered for switch |

| Up to 3 months of age | Switch after 14–21 days Duration of treatment - 4–6 weeks (for both OM and SA) |

Switch after 21 days Duration of treatment - 4–6 weeks (for both OM and SA) |

| 3 months of age – time to switch and duration | Switch after 24–48 h of clinical improvement Total duration: OM: 3–4 weeks (MRSA –6 weeks) SA: 2–3 weeks |

2 weeks of IV antibiotics and then switch to oral to cover the total duration of treatment of 4–6 weeks (for both OM and SA) |

| 9. Follow-up | CRP Longer follow-up is required in infants and complicated infections. Follow-up imaging (USG/MRI) may be required. |

End point of therapy is difficult to determine in complicated infections which can be based on normal CRP and improvement in symptoms Follow-up with the orthopaedic surgeon to address on-going sequelae. |

CRP: C-reactive protein, CBC: Complete blood count, ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, USG: Ultrasound, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, OM: Osteomyelitis, SA: Septic arthritis, MRSA: Methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus

| Age | Empirical IV antibiotic treatment |

|---|---|

| <3 months | Cefazolin and gentamicin (alternative – ASP + cefotaxime) |

| 3 months–5 years | Cefuroxime/cefazolin, in non Kingella regions – add clindamycin; Alternatives: Ceftriaxone or ASP or amoxicillin-clavulanate or ampicillin-sulbactam |

| >5 years | Cefazolin or ASP or clindamycin (high MRSA prevalence) |

MRSA: Methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus, ASP: Antistaphylococcal penicillin.

Surgical interventions

Include: Arthrotomy, arthroscopy, arthrocentesis and lavage – chosen based on institutional expertise and clinical condition.[3]

Complications/sequelae

Limping, deformity, pyomyositis, chronic pain, rigidity and chronic

Recommended follow-up intervals with paediatrician and orthopaedic surgeons post-discharge are as follows: 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 12 months after discharge

Pain-free normal activity is the end point to end follow-up.

Physical therapy

Support and protection devices such as removable cast and boot case depend on the site and severity of bone and joint infections. Instructions are given to avoid weight-bearing and encourage passive movements to prevent rigidity.

Management of bone and joint infections is by a multidisciplinary approach which includes a team of paediatrician, paediatric orthopaedic surgeons, paediatric infectious disease specialists and rehabilitation.

CONCLUSION

Paediatric osteoarticular infections always pose diagnostic challenges due to their non-specific clinical presentation. Due to the non-availability of ‘gold standard’ diagnostic tests, many diagnostic algorithms were proposed which were never a substitute for clinical decision-making. Recommendations in the literature are based on expert opinions, case series and descriptive studies. There is a need for large multicentric randomised controlled trials and prospective studies for better understanding of paediatric osteoarticular infections to decrease morbidity and mortality.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Bhaskar Shenoy is on the editorial board of the Journal.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Paediatric bone and joint infection. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2:7-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Septic arthritis in children: Updated epidemiologic, microbiologic, clinical and therapeutic correlations. Pediatr Neonatol. 2020;61:325-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESPID practice guidelines bone and joint infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:788-99.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen's emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice In: Bone and joint infections. United States: John Wiley and Sons; 2018. p. :1693-709.e2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteoarticular infections in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:557-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]