Translate this page into:

A systematic review on impact of combined spinal epidural analgesia on neonatal outcomes during caesarean section

*Corresponding author: Dr. Lata A Shah, Department of Anaesthesiology, Mahadevappa Rampure Medical College, Kalaburgi 585-105, Karnataka, India. latads@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Dharanappa D, Gadgade A, Shah LA. A systematic review on impact of combined spinal epidural analgesia on neonatal outcomes during caesarean section. Karnataka Paediatr J. doi: 10.25259/KPJ_6_2025

Abstract

Background

Combined spinal epidural (CSE) analgesia has grown in popularity as a labour analgesic. The present systematic review assesses neonatal outcomes linked to CSE analgesia in caesarean sections, emphasising foetal heart rate (FHR) abnormalities, Apgar scores and additional neonatal parameters.

Methods

Publicly accessible English databases, including PubMed and Google Scholar, were searched from 2005 to 2022. A total of 120 research documents were mined, with nine articles selected according to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results

Findings indicate that temporary FHR alterations, such as bradycardia, delayed decelerations, decreased accelerations and increased neonatal intensive care unit admission, are linked to CSE analgesia. No significant effect was observed on Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min nor on neonatal birth weights.

Conclusion

The study found that quick onset analgesia and flexibility of CSE analgesia justify its use during caesarean sections; however, medication selection and maternal monitoring are essential. Assessing its long-term neonatal consequences and high-risk applications needs more investigation.

Keywords

Caesarean section

Combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia

Combined spinal epidural

Neonatal outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Labour pain is regarded as the most intense agony. Labour pain contributes to persistent pain, postpartum stress syndrome and adverse psychological and physiological effects.[1] Pain and anxiety trigger the release of adrenaline and prolong labour; 25% rise in noradrenaline levels results in a 50% reduction in uterine blood flow. In addition to an increase in oxygen demand, the maternal heart rate and systemic resistance to blood flow will also be enhanced.[2]

Caesarean section contributes to 21% of childbirths globally.[3] Neuraxial analgesia is widely regarded as the gold standard for labour analgesia since it ensures the most efficient pain management during labour.[4] Neuraxial procedures help to avoid the risks that are inherent to airway manipulation, like aspiration and the ‘cannot intubate cannot ventilate’ scenario.[5] Common methods of neuraxial anaesthesia include single-shot spinal or epidural injection and continuous epidural infusion. Spinal anaesthesia administered as a single injection provides quick onset of action and is reasonably simple to administer during caesarean section. However, spinal anaesthesia is accompanied by muscle relaxation hypotension and does not allow for the extension of the block.[6] The onset of the block of epidural analgesia (EA) occurs at a significantly slower rate. The epidural approach usually involves the placement of a catheter, which allows continuous infusion.[7]

Combined spinal epidural (CSE) involves the subarachnoid injection of local anaesthetics and placement of a catheter into the epidural space, which can be used to administer local anaesthetics to prolong the duration of spinal anaesthesia.[8] The benefit of the CSE is the swift attainment of neuraxial block through the spinal component, whereas the epidural catheter facilitates the extension or alteration of the blockage. The advantages of employing CSE for analgesia during labour encompass the swift start of relieving pain relative to traditional epidural methods (especially in the later stages of labour) and a continuation of ambulation capability.[9] Studies have shown that CSE is superior to only epidurals for caesarean sections with regards to analgesia and muscular relaxation. The local anaesthetic required is reduced with CSE compared to only epidurals for caesarean sections.[10] The advantages of continuous spinal epidural compared to a single-shot spinal anaesthetic for caesarean section have been considerably challenging to substantiate. Nonetheless, the CSE approach is particularly advantageous in scenarios where surgical duration is anticipated to exceed that of a single-shot spinal block.[11] However, CSE has its own set of limitations. It can result in neurological complications, post-dural migraines and infections.[9] There are a limited number of comparative studies which were available concerning neonatal outcomes. Hence, the present systematic review aims to examine the neonatal outcomes of infants born following the administration of CSE anaesthesia during caesarean section.

METHODOLOGY

Literature search

Using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses- systematic review and meta-analysis guidelines, the present study search to evaluate the neonatal outcomes of CSE injected during caesarean sections was conducted.[12] The inclusion criteria for screening the research articles include randomised and observational studies to understand the impact of CSE on newborn infants. The exclusive criteria include non-randomised studies, uncontrolled studies, laboratory studies and case reports. Literature searches are done only in English databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar. The search was confined to a period from 2005 to 2022. The main keywords for PubMed are CSE analgesia, neonatal outcomes and caesarean section. The pertinent medical subject headings (MeSH) used are (‘combined-spinal-epidural’[Title/Abstract] OR (‘combinable’[All Fields] OR ‘combined’[All Fields] OR ‘combination’[All Fields] OR ‘combinational’[All Fields] OR ‘combinations’[All Fields] OR ‘combinative’[All Fields] OR ‘combine’[All Fields] OR ‘Combined’[All Fields] OR ‘combines’[All Fields] OR ‘combining’[All Fields]) AND ‘spinal-epidural’[All Fields]) AND ‘CSE’[Title/Abstract]) OR (‘combined-spinal-epidural’[All Fields] AND ‘CSE’[Title/Abstract]) OR ‘combined-spinal-epidural’[Title/Abstract]) AND (‘neonatal outcomes’[Title/Abstract] OR ‘neonat* outcom*’[Title/Abstract]). To find other related studies, we thoroughly reviewed our options, selected the study with a larger sample size or the most recent publication for our research samples and then looked further into the publications’ references to find comparable studies.

Selection and screening

The screening approach consists of research articles performed separately by two researchers. Research documents were screened in the first step based on the title and abstract. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the selected research documents were thoroughly reviewed and articles not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded from the study. The research articles were excluded if the study was about the usage of CSE analgesia for other surgeries. Finally, the researcher independently retrieved pertinent data from the included studies using a pre-designed data-collecting form. Any differences in the data collected were sorted out through discussion. The primary contents of the data collection form include the title of the research article, author name, year of publication, study design, indication, inclusion and exclusion criteria of the selected article, sample size, methodology, results, neonatal outcomes and conclusion of the study [Table 1].

Risk of bias (ROB) analysis

For randomised studies, the ROB was assessed using the Cochrane ROB[13] in three potential domains-selection, performance and outcomes. The observational studies were assessed using Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale cohort studies on three main selection, comparability and outcomes.[14] The overall rating for each question was rated as Yes (implies high quality), No (indicates quality or particular criteria not fulfilled) and Unclear (suggests particular criteria in the selected paper not accurate) [Supplementary Tables I and II].

RESULTS

Literature search and study characteristics

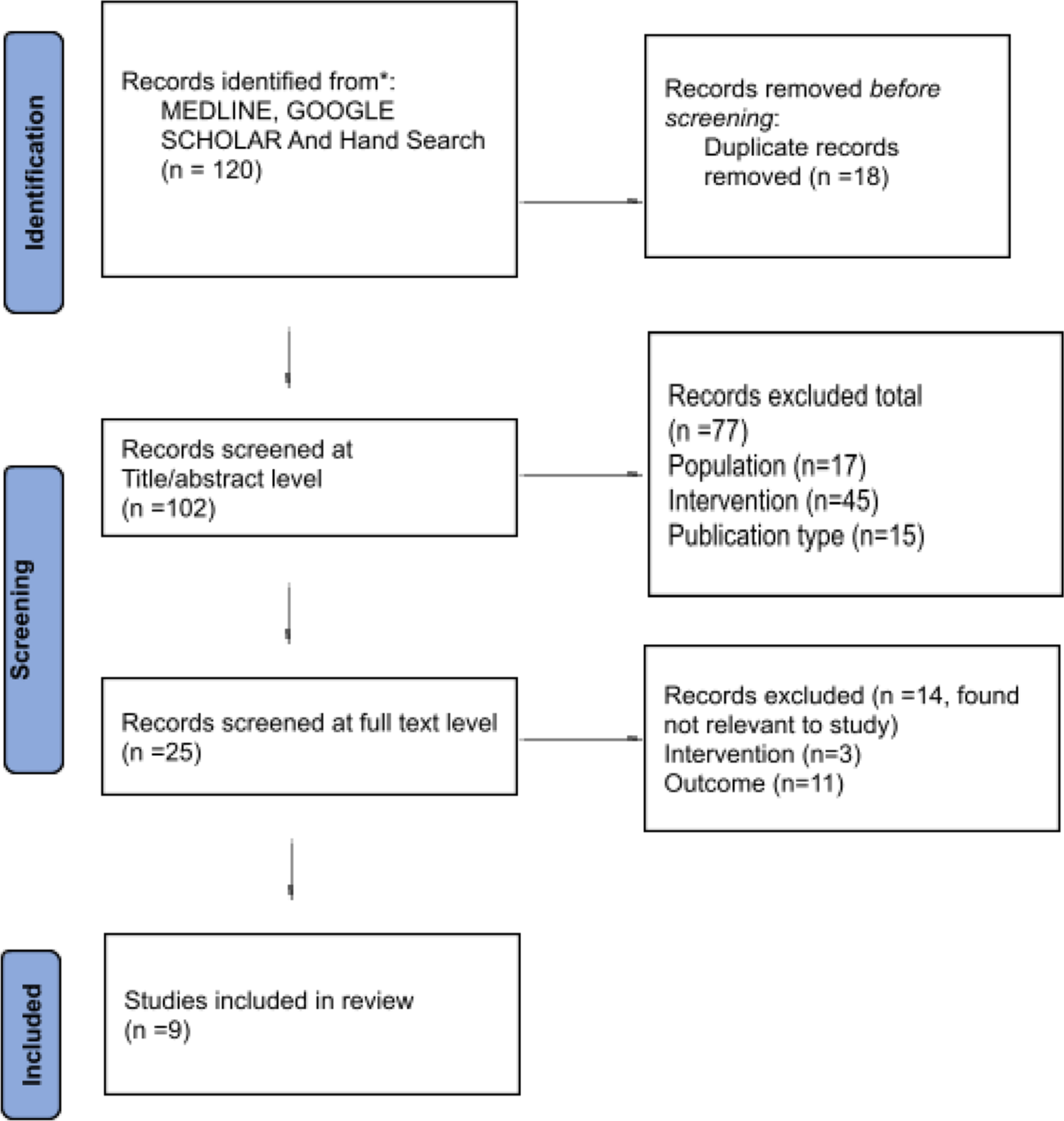

A summary of the systemic review search strategy with inclusion and exclusion articles was presented in a flowchart [Figure 1]. From English databases, 120 studies were retrieved, and 18 duplicates were discarded. After the initial article title and abstract screening, 77 studies were excluded. Further, in the full-text analysis, 14 non-relevant articles were excluded, and nine research articles were selected for the final study. Of the included studies, four studies were randomised controlled studies[15-18] and five studies were retrospective cohort studies.[19-23]

| Aim | Study design | Intervention | Comparator | Sample size | Neonatal outcomes | Conclusion | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To evaluate the effects of CSE analgesia versus the absence of analgesia during spontaneous labour | Retrospective cohort study | CSE analgesia in nulliparous and multiparous women | No analgesia in nulliparous and multiparous women | Nulliparous (3334) multiparous (1913) CSE- (2045, 996) No analgesia (1289, 917) |

Both nulliparous and multiparous women had Apgar scores below 7 at 1 min (aOR, 1.85 and 2.65) and multiparous women had umbilical arterial blood gas pH values below 7.15 (aOR, 2.69) and <7.10 (aOR, 3.69). | The study found that pregnant women who had CSE analgesia during labour had a number of higher risks for obstetric and neonatal outcomes, although there was no discernible change in the rate of caesarean birth or Apgar score <7 at 5 min. | [23] |

| To assess the impact of CSE analgesia on labour outcomes. | Prospective observational study | CSE | Non-CSE | CSE (n=55) or Non-CSE (n=55) | Foetal discomfort was the primary reason for EMLSCS, with 14.5% and 10.9% of instances in the CSE and no analgesia groups, respectively. For the remaining cases in both groups, EMLSCS was recommended due to inadequate improvement. At 1 min, 3 neonates in the CSE group and 2 in the no analgesia group had Apgar scores below 7 without any significant statistical correlation. All neonates achieved an Apgar score of <7 at 5 min. |

The length of labour, the rate of instrumental vaginal delivery and emergency caesarean section, and the neonatal outcome did not change significantly between parturients who got CSE for labour and those who did not receive analgesia. | [20] |

| To examine the impact of EA and CSE on maternal intrapartum temperature and neonatal Apgar scores | RCT | CSE analgesia | EA | 400 healthy nullipara patients | No changes were identified in newborn weight or neonatal antibiotic use or Apgar scores at 1 min and 5 min concerning neonatal outcomes. 1-min Apgar score or 5-min Apgar score | Our data indicate that CSE is linked to a reduced risk of intrapartum fever compared to EA. | [15] |

| To evaluate the effects of intrapartum EA compared to CSE on FHR variations in pregnancies susceptible to uteroplacental insufficiency. | Retrospective study | CSE analgesia | Intrapartum EA | EA-110 patients CSE-127 patients | In terms of neonatal outcomes, the rate of admission to the NICU was significantly higher in the CSE group (29.5%) than in the EA group (16.5%). Both groups exhibited comparable mean arterial umbilical cord pH, with EA at 7.220±0.082 and CSE at 7.194±0.082 and arterial CO2 levels, with EA at 58.9±12.1 mmHg and CSE at 60.9±12.3 mmHg. | The study concludes that CSE and EA both led to a rise in the FHR anomalies. There was no difference in the necessity for foetal interventions and the adverse consequences of maternal | [22] |

| This study aims to compare CSE with EA regarding their effects on the length of stage I labour, as well as the outcomes for mothers and newborns. | Prospective cohort study | CSE | Epidural | Combined spinal–epidural group -176 patients and epidural group-224 patients. | The findings demonstrate VAS score <4 after 5 min (P <0.001) and reduced VAS values following the initial administration of analgesia. No disparities were seen in the remaining outcomes. | The combination of spinal-epidural anaesthesia with subarachnoid SUF may not decrease the duration of stage I labour; nevertheless, investigation indicated that it seemed to have a lesser impact on uterine contractility. It had a quicker onset and greater efficacy, without any associated increase in maternal or neonatal problems. |

[21] |

| The study evaluated FHR patterns, Apgar ratings and umbilical cord gas levels after spinal-epidural versus epidural labour analgesia. | RCT | CSE | EA | CSE (n=62) or EA (n=53). | No substantial variations were seen in FHR patterns, Apgar ratings, or the acid-base state of umbilical artery and vein across the groups. In both the CSE and epidural groups, there was a notablerise in the occurrence of abnormal FHR patterns post-neuraxial analgesia; two instances prior compared to eight subsequent in the CSE group, and zero prior compared to eleven subsequent in the epidural group. The alterations included an increase in decelerations (CSE group: Nine before and 14 subsequent to analgesia; epidural group: four before and 16 subsequent to), an increase in late decelerations (CSE group: Zero before and seven subsequent to analgesia; epidural group: Zero before and eight subsequent to) and a decrease in the rate of accelerations (CSE group: 2.2±6.7/h before and 9.9±6.1/h after analgesia; epidural group: 11.0±7.3/h before and 8.4±5.9/h following analgesia administration). | The alterations in FHR did not influence neonatal outcomes in this healthy cohort. | [16] |

| The purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that decreasing the spinal dose of local anaesthetics should result in anaesthesia that is just as effective and less hypotension in the mother. | RCT | HIGH-group CSE anaesthesia was performed using 9.5 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine combined with 2.5 microg SUF | LOW-group CSE anaesthesia was performed using 6.5 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine combined with 2.5 microg SUF | 50 patients | No difference was observed in Apgar score at 1 min and 5 min, neonatal birthweight, UA pH, UA base excess and UA Pco2 between both the groups | The study concludes that conclude that small-dose analgesia contributes for better maternal hemodynamic stability and neonatal outcomes. | [17] |

| To assess whether removing SUF from the intrathecal space reduces the incidence of unfavourable FHR changes, the study retrospectively compared a protocol that used both SUF and ropivacaine intrathecally with a procedure that only used ropivacaine intrathecally and SUF epidurally. | Retrospective | SUF was used epidurally (SEP) | SUF intrathecal protocol | 520 cardiotocographic tracings | The use of SUF epidurally, as opposed to intrathecally, resulted in a reduced incidence of adverse changes in foetal heart tracings. This is evidenced by a higher percentage of normal reassuring tracings (74.5% compared to 60.4% with intrathecal administration;P=0.007), a lower occurrence of bradycardia (7.5% versus 14.1%;P=0.035) and an increased percentage of tracings showing three or more accelerations in FHR within 45 min (93.5% versus 83.9%;P=0.003), along with fewer episodes of tachycardia (3.5% vs. 11.4%;P=0.005). No differences were observed in labour and neonatal outcomes. No significant difference in Apgar scores, nor in admissions to the neonatal care unit. |

The study concludes that CSE utilising a local anaesthetic and excluding SUF from the epidural space is associated with improved CTG outcomes, demonstrating more accelerations, reduced bradycardia and decreased tachycardia compared to scenarios where SUF is administered intrathecally. | [19] |

| The study posited that administering intrathecal SUF at a dose of 7.5 micrograms is more likely to result in a no reassuring FHR tracing compared to a lower dose of spinal SUF in conjunction with bupivacaine or EA. | RCT | Group 2 – Initial intrathecal analgesia consisted of 2.5 mg of bupivacaine, 2.5 µg of epinephrine and 1.5 µg of SUF. SUF-spinal analgesia consisted of 7.5 µg of SUF |

EPD group -EA 12.5 mg of bupivacaine, 12.5 µg of epinephrine and 7.5 µg of SUF | 300 patients | The quality of analgesia, labour, neonatal outcomes and side effects were documented. In the SUF group, 24% of patients exhibited FHR abnormalities (bradycardia or late decelerations) within the 1st h following the initiation of analgesia, in contrast to 12% in the Group 2 and 11% in the EPD group. Uterine hyperactivity was observed in 12% of parturient in the SUF group, compared to only 2% in the other groups. The onset of analgesia was more rapid in both CSE groups compared to the EPD group. In the BSE group, 29% of patients experienced severe hypotension, necessitating IV ephedrine, compared to 7% in the EPD group and 12% in the SUF group. All these differences attained statistical significance | The current findings support earlier advisories regarding the use of high doses (7.5 micrograms or more) of spinal SUF in CSE, due to the associated risks of uterine hyperactivity and FHR abnormalities. | [18] |

CSE: Combined spinal epidural, aOR: Adjusted odd ratio, EA: Epidural analgesia, RCT: Randomised controlled trial, NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit, FHR: Foetal heart rate, SUF: Sufentanil, EMLSCS: Emergency lower segment caesarean section, VAS: Visual analog scale, UA: Urine analysis, CTG: Cardiotocography,

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for the systematic review which included searches of databases.

Foetal heart rate (FHR) abnormalities

The present study evaluated the impact of CSE on patterns of FHR after caesarean sections. A comparative study conducted to study the impact of CSE versus intrapartum epidural analgesia (EA) demonstrated a notable rise in FHR Category II patterns among both the CSE and EA cohorts. However, CSE correlated with elevated neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission rates (29.5% vs. 16.4%).[22] Another study similarly noted that both CSE and EA resulted in substantial increases in FHR anomalies including delayed decelerations, reduced accelerations and bradycardia; however, these changes did not adversely affect neonatal outcomes in a healthy cohort.[16] Comparative studies were conducted to evaluate the different methodologies on the impact of CSE on FHR. Van de Velde et al., in 2004, noted that high-dose intrathecal sufentanil (7.5 µg) in CSE anaesthesia was associated with heightened FHR anomalies, uterine hyperactivity (12% compared to 2% in lower-dose groups) and bradycardia, underscoring the dangers of substantial intrathecal doses.[18] A study comparing intrathecal and epidural sufentanil revealed that intrathecal administration was associated with a greater frequency of FHR abnormalities, including a lower percentage of reassuring tracings (60.4% vs. 74.5%, P= 0.007), a higher incidence of bradycardia episodes (14.1% vs. 7.5%, P = 0.035) and an increased occurrence of tachycardia (11.4% vs. 3.5%, P = 0.005).[19]

CSE impact on Apgar score

Five included studies evaluated the impact of CSE on Apgar scores of neonates. A retrospective cohort study compared the administration of CSE analgesia in nulliparous and multiparous women, revealing no statistically significant variance in the Apgar scores at 5 min (> 7) or in the caesarean section rates.[23] Likewise, another study found no differences between the newborn’s weight, antibacterial medications administration and Apgar scores at 1 min and 5 min.[15] Singh et al. found no discernible variations in Apgar scores at 1 min and 5 min. Apgar score was less than 7 in both groups at 1 min and 5 min indicating similar newborn outcomes between the CSE and non-CSE groups.[20] Furthermore, Van de Velde et al., in 2006, observed similarly no major discernibility between the groups in terms of newborn outcomes, such as Apgar scores and neonatal birth weight.[17] A study evaluating maternal and neonatal outcomes using the Visual Analogue Score found no significant differences, except for pruritus, which occurred more frequently in the CSE group (18% vs. 7%).[21] These findings consistently show that CSE has no appreciable negative effects on newborn outcomes.

ROB analysis

No major ROB was observed in all the studies. For cohort studies, outcomes were unclear or not completely fulfilled in three studies.[19-21] In randomised controlled studies, selection bias was unclear in two studies.[17,18]

DISCUSSION

In obstetric practice, CSE anaesthesia – which combines the malleability of continuous epidural infusion with the quick onset of spinal anaesthesia – has grown in popularity as an anaesthetic treatment.[24] To improve maternal and neonatal care, it is essential to understand the effects of CSE anaesthesia on the outcomes of neonates.

The review’s findings emphasise the intricate relationship between CSE anaesthesia and FHR anomalies and its negligible effect on Apgar scores. Numerous studies indicate that neuraxial analgesia, which includes CSE anaesthesia correlates with transient FHR alterations, including bradycardia, delayed decelerations, and diminished accelerations.[25,26] Maetzold et al., documented notable increases in FHR Category II patterns after the administration of neuraxial analgesia, with comparable trends evident in both the CSE anaesthesia and EA cohorts. Nonetheless, CSE correlated with increased NICU admission rates, indicating that these transient FHR alterations may sometimes carry clinical significance.[22] The influence of high-dose intrathecal sufentanil on these abnormalities is significant, indicating a markedly increased occurrence of bradycardia with elevated intrathecal doses.[18] The findings emphasise the necessity for careful selection and dosing of intrathecal agents during CSE anaesthesia to reduce potential foetal effects.

Across studies, newborn outcomes – as measured by Apgar scores – remained essentially the same despite the noted FHR reductions. All the included studies observed no appreciable variations in Apgar scores and other neonatal outcomes such as birthweight between CSE and other control groups.[15,20,23] This congruence indicates that although CSE could elicit short-lived FHR anomalies, these alterations do not usually result in severe impairment of newborn health, therefore confirming the safety of CSE in terms of Apgar ratings and newborn well-being.

Apart from these results, it is crucial to recognise any possible limitations and complicating variables. Possible confounding factors include differences in study design, demographics and anaesthetic procedures included trials. It was difficult to draw direct comparisons since variables such as multiple maternal medical conditions, gestational age and obstetric justifications for caesarean section were not consistently controlled. Furthermore, the reviewed studies did not consistently assess neonatal outcomes, including long-term impact on the neurodevelopmental of the newborn.

CONCLUSION

This review emphasises the need for a combined strategy while applying CSE analgesia during caesarean procedures. Although CSE causes temporary FHR abnormality, however it has no significant impact on neonatal outcomes. A customised analgesia strategy that prioritises cautious medication selection and close observation can optimise CSE benefits while lowering risks for both maternal and neonates.

Authors’ contributions

DD: Data extraction and compiling; AG: Reviewing of the data; KR: Manuscript preparation; LS: Study design and reviewing of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Maintenance of epidural labour analgesia: The old, the new and the future. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 20I7;. ;31:15-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A review article on epidural analgesia for labor pain management: A systematic review. Int J Surg Open. 2020;24:100-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global increased cesarean section rates and public health implications: A call to action. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:e1274.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The current role of general anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2021;11:18-27.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Failed tracheal intubation during obstetric general anaesthesia: A literature review. Int J Obstet Anaesth. 2015;24:356-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Techniques for preventing hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8:CD002251.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidural analgesia for labor: Current techniques. Local Reg Anesth. 2010;3:143-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combined spinal-epidural techniques. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2007;7:38-41.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Current status of the combined spinal-epidural technique in obstetrics and surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2023;37:189-98.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSE versus epidural analgesia in labour In: , ed. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons. Ltd.; 2003. p. :CD003401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combined spinal-epidural vs. Spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section: Meta-analysis and trial-sequential analysis. Anaesthesia. 2018;73:875-88.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;29:372.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/. https://web.archive.org/web/20210716121605id_/http://www3.med.unipmn.it/dispense_ebm/2009-2010/Corso%20Perfezionamento%20EBM_Faggiano/NOS_oxford.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 28]

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of combined spinal-epidural analgesia on maternal intrapartum temperature: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22:352.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetal effects of combined spinal-epidural vs epidural labour analgesia: A prospective, randomised double-blind study. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:458-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery: Dose-dependent effects of hyperbaric bupivacaine on maternal hemodynamics. Anaesth Analg. 2006;103:187-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrathecal sufentanil and fetal heart rate abnormalities: A double-blind, double placebo-controlled trial comparing two forms of combined spinal epidural analgesia with epidural analgesia in labor. Anaesth Analg. 2004;98:1153-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combined spinal epidural analgesia for labor using sufentanil epidurally versus intrathecally: A retrospective study on the influence on fetal heart trace. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:481-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combined spinal-epidural analgesia in labour: Its effects on delivery outcome. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2016;66:259-64.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of combined spinal-epidural analgesia on first stage of labor: A cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:3559-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of combined spinal epidural versus epidural analgesia on fetal heart rate in laboring patients at risk for uteroplacental insufficiency. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35:46-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delivery mode and maternal and neonatal outcomes of combined spinal-epidural analgesia compared with no analgesia in spontaneous labor: A single-center observational study in Japan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46:425-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidural analgesia compared with combined spinal-epidural analgesia during labor in nulliparous women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1715-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetal heart rate changes and labor neuraxial analgesia: A machine learning approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:329.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of epidural analgesia on the fetal heart rate. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:160-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]