Translate this page into:

An unusual deep seated haemangioma successfully treated with propranolol

*Corresponding author: Sujatha Ramabhatta, Professor, Department of Paediatrics, K. C. General Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. sujatharamabhatta@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Dudala K, Ramabhatta S, Lakshmipathy SR, Raghunandan BG, Rashmi K, Mol P. An unusual deep seated haemangioma successfully treated with propranolol. Karnataka Paediatr J 2021;36:129-31.

Abstract

Infantile hemangiomas (IH) are most common vascular tumors. It usually resolves on its own, treatment becomes necessary if there is disease progression. Oral propranolol is a medical therapeutic option for complicated IH with impressive efficacy and generally good tolerance. We report a case of deep seated IH of the cheek in a 4 month old successfully treated with propranolol.

Keywords

Hemangioma

Propranolol

Medical Therapy

INTRODUCTION

Haemangioma are tumours of endothelial cells that appear at birth, within the 1st few weeks after birth. Infantile haemangiomas (IH) initially proliferate and begin to regress by the 1st year of life.[1] Although majority of them are clinically insignificant, some may be life threatening, or may have associated congenital structural anomalies. Early and effective management is required in case IH progresses to ulceration, deformation, or functional impairment.

Corticosteroids have been replaced by propranolol since it has proved more effective with fewer side effects.[2] Propranolol given orally at 2–3 mg/kg/day shortens the disease course. The previous standard therapeutic options include physical measures such as laser and cryosurgery and systemic corticosteroids.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 4-month-old male exclusively breast-fed was admitted with complaints of left cheek swelling for 4 days without any discoloration or pain during feeding. There was no history suggestive of bleeding or loss of weight. On examination, the child was playful and active. The facial swelling was firm to hard, measuring 7 cm × 5 cm and mobile. Oral mucosa was normal. There was no evidence of haemangiomas on the face. Abdominal examination was normal.

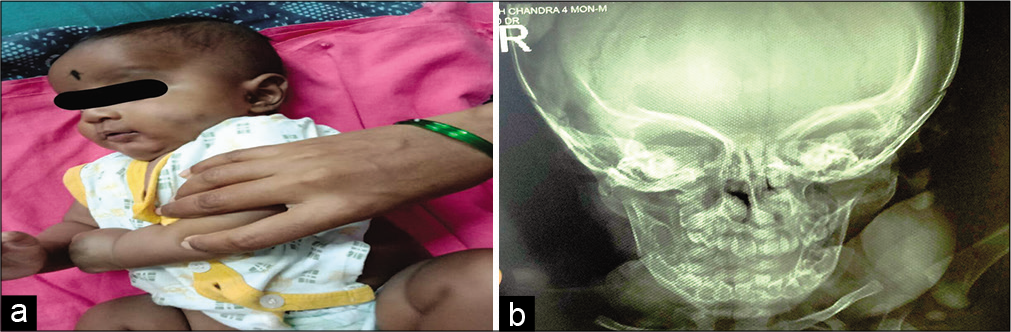

Complete hemogram and coagulation profile were normal. The skull X-ray revealed an encapsulated swelling noted over the left side of the face (measurements 7 cm × 5 cm) pushing the mandible toward medial side without obvious hyperostosis, lytic/sclerosis of the underlying bone as shown in [Figures 1a and b].

- (a) Child picture before treatment. (b) Child X-ray before treatment.

The ultrasonogram of the left cheek revealed a well-defined heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion with no internal vascularity measuring 20 × 23 mm in soft tissue of the left buccal region without calcifications. The abdominal scan did not reveal haemangioma of internal organs. Fine-needle aspiration showed predominantly haemorrhage suggestive of haemangioma.

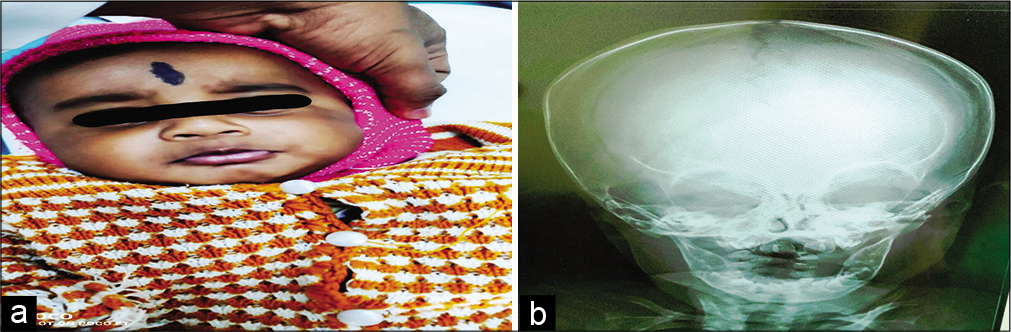

The baby was started with propranolol 1 mg/kg/day for 1 week with monitoring of glucose, heart rate and blood pressure, and increased to 2 mg/kg/day in three divided doses. The decision to treat with the drug was made because of the size, mass effect and location. At the end of 2 months, there was no evidence of any facial swelling and an X-ray showed the absence of soft tissue swelling with the correction of the mandibular ramus, as shown in [Figures 2a and b]. The child is on continuous follow-up.

- (a) Child picture after treatment. (b) Child X-ray after treatment.

DISCUSSION

IH account for 4–10% of soft tissue tumours among infants.[3] IH commonly arise from the head, neck, and extremities. Depending on morphology, they are typed as focal, segmental and indeterminate.[4] The most common variant is focal IH. They are single, discrete, and raised unlike the segmental IH which are more extensive, flat, and conform to anatomical or developmental site. Based on the depth of lesion, they are classified as superficial, deep, and mixed. Colour varies with the depth of the lesion, ranging from bright red, purple, blue, or normal skin colour. According to the size of the vascular channels, IH is grouped as capillary and cavernous.[5]

Pathogenesis of IH is not clearly understood. Both endothelial and vascular factors are believed to be responsible for angiogenesis. Erythrocyte-type glucose transporter protein GLUT-1 marker is explicit of haemangiomas.[6] In patients with proliferative haemangiomas, they have found increased markers of VEGF receptor-2.[7]

In IH, there is an initial proliferative phase followed by stationary phase and finally the involution phase. Most haemangiomas grow in the first 5 months and start involution by the end of 1 year. Common complications are ulceration and functional impairment in the form of airway obstruction, visual compromise, feeding difficulties, and auditory canal obstruction.

Medical therapy of IH includes topical agents and systemic medications. Propranolol a non-selective beta-blocker is the drug of choice, given for 6 months–1 year in the dose of 1–2 mg/kg in divided doses with close monitoring of heart rate and blood glucose. As a topical applicant 0.5% timolol is used for treating IH. Propranolol and timolol are helpful in decreasing the size and stop further progression of haemangioma, thereby, making it accessible to surgery when needed.[8] Surgery is indicated in cases where medical therapy fails or requires urgent intervention.[9]

CONCLUSION

IH is a common benign vascular tumour of infancy and early childhood. Oral beta-blockers are safe and effective, with minimal side effects even in poor resource settings.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cellular and extracellular markers of hemangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:529-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous hemangiomas in children: Diagnosis and conservative management. JAMA. 1965;194:523-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Propranolol therapy for infantile hemangioma. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:307-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemangiomas of infancy: Clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vascular malformations and hemangiomas: A practical approach in a multidisciplinary clinic. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:597-608.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLUT1: A newly discovered immunohistochemical marker for juvenile hemangiomas. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:11-22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and vascular anomalies. Lymphat Res Biol. 2005;3:234-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propranolol reduces infantile hemangioma volume and vessel density. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:338-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infantile haemangioma and β-blockers in otolaryngology. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:236-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]